When the Portuguese set sail in search of spices, the name they were given for Siam simply meant ‘new city‘

Manote Tripathi

The Nation

July 25, 2011

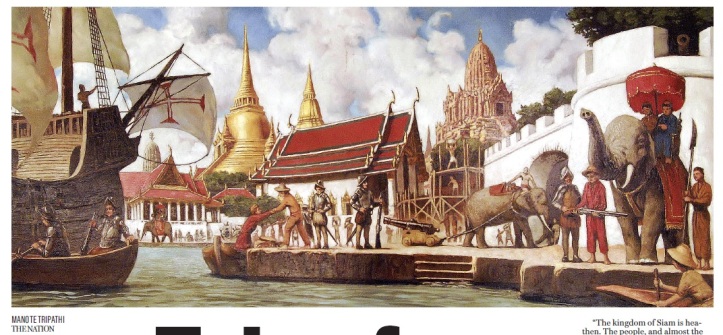

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to enter Ayutthaya in 1511. Today, five centuries on, Thailand and Portugal are the closest of friends, so much so that a Thai pavilion is about to be constructed in the

heart of Lisbon to celebrate the five centuries of diplomatic ties.

Yet many Portuguese today are decidedly ignorant about Thailand. Generalities abound, with many believing that Bangkok is in Indochina, bamboo is everywhere, the city is criss-crossed with rivers and canals, and the movie “Tears of the Black Tiger” is great.

Things were even worse in the 15th century just before the Portuguese landed ashore in Ayutthaya. They had been given the name of the country by their Arab traders and informants and told that Siam was in fact called Xarnauz (from the Persian word Shahr-i-nao meaning “new city”). Our capital Odia was ruled by a Christian king. Its distance from Calicut was 50 days with a good wind. The King could muster 20,000 fighting men and 4,000 horses and owned 400 war-elephants. Xarnauz had lots of spices and benzoin, worth three cruzados the frazila, as also much aloe, worth 25 cruzados the frazila.

Portuguese historian and former cultural counsellor of the Portuguese embassy in Bangkok, Jorge Morbey came across these facts while researching the history of Siam-Portuguese relations. Together with Thai historians, Morbey unveiled his findings at the recent conference on “500 Years of Thai-Portuguese Relations” organised by the Portuguese Embassy and the Fine Arts Department at the Trang Hotel in Bangkok.

The interest in Siam and other eastern kingdoms was part of Portugal’s grand scheme of finding maritime trade routes to the East. It was not easy to take the land routes, which were controlled by the Ottomans.

In 1497, King Manuel sent four ships to the East in search of spices. The captains were Vasco da Gama, his brother Paulo and Nicolao Coelho. Vasco da Gama himself did not sail beyond the Indian seas, but his expedition (1497-99) was recorded in a trip itinerary written by Álvaro Velho, a crew member of da Gama’s fleet, which referred to Siam as “Xarnauz”.

A clearer image of Siam was to come from the 16th-century Portuguese author Tome Pires (1465-1524), an apothecary to Prince Afonso, son of King John II of Portugal. He mentioned Siam at length in his landmark account of his Malay-Indonesia travels entitled “Suma Oriental” (“Summa of the East, from the Red Sea up to the Chinese”), which was written while he was in Malacca and India between 1512 and 1515.

He went to India in 1511 invested as “factor of drugs”, the Eastern commodities that were an important element of what is generally called “the spice trade”. In Malacca and Cochin he avidly collected and documented information from the MalayIndonesia area, and personally visited Java, Sumatra and Maluku.

The first comprehensive European description of the Portuguese East and Malaysia, the book covers a lot of ground: historical, geographical, ethnographic, botanical, economic and commercial.

“The kingdom of Siam is heathen. The people, and almost the language, are like those of Pegu. They are considered to be prudent folk of good counsel. The merchants know a great deal about merchandise. They are tall, swarthy men, shorn like those of Pegu. The kingdom is justly ruled. The king is always is residence in the city of Odia. He is a hunter. He is very ceremonious with strangers; he is more free and easy with the natives.”

Pires wrote that there were very few Moors in Siam. The Siamese did not like them. There were, however, Arabs, Persians, Bengalese, many Kling, Chinese and other nationalities. And all the Siamese trade was on the China side, and in Pase, Pedir and Bengal. The Moors were in the seaports and obedient to their own lords, and constantly made war on the Siamese.

Morbey asserts that of all foreigners in Ayutthaya, the Portuguese were well liked by Siamese kings including King Mongkut (Rama IV) of the Bangkok period. The historian notes Rama IV’s satisfaction with the Portuguese settlement in his land.

“When the great wars happened, which ruined Ayuthia, the ancient capital of this Kingdom, all the European residents in Siam abandoned the country, with the exception of Portuguese,” King Mongkut wrote in one of his speeches.

Morbey observes that in general, the Portuguese residents in Siam were Eurasian Christians whose cultural background was heavily based on the Portuguese language and the Catholic Roman religion.

In 1729, 38 years before the fall of Ayutthaya, 12 Portuguese families lived in Bangkok, in the Rosary Bandel, says Morbey. Siam saw the Portuguese as its close allies because they were mercenaries in the Siamese army in important wars. It’s hard to find out how many Portuguese soldiers were in the Ayutthaya army when the city fell. But Morbey notes that there were 79 Portuguese names in the army of King Taksin of Thonburi.

Others were shipbuilders, merchants and translators, areas useful to Siam’s foreign and trade affairs. The first king of the Bangkok period, Rama I, in a letter to Portugal’s Queen D Maria I in 1786, expressed his gratitude for Portuguese support in Siam’s battles with Burma. In that letter, the king asked to buy 3,000 rifles from the Governor of Goa. The governor of Goa sent not just weapons to Bangkok, but shipbuilders and carpenters and more consuls. Their descendants still remain in Bangkok. These days they are known for their fine creations of Thai-Portuguese desserts.

Great article, thank you for this write up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for reading.

LikeLike