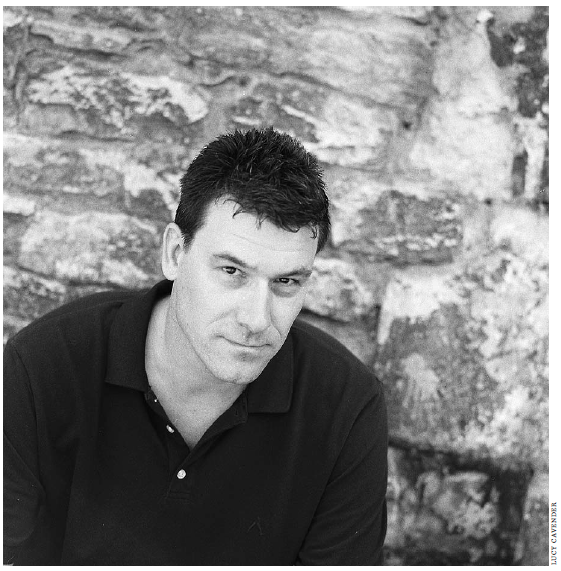

Author Paul French sheds light on the brutal murder of a British teenager in 1930s Peking and explains why the investigation fizzled out

MANOTE TRIPATHI

THE NATION

Singapore

Dec 24, 2012

Life in the pre-1949 China has always fascinated British author Paul French. Writing about it, he admits, is a daunting task, especially given the plethora of books on Chinese history. But French stumbled upon an original subject that has set him apart from other Western authors of Chinese history: the unresolved murder of a British teenager in Peking in 1937. With his new book titled “Midnight in Peking”, French sets out to resolve this elusive case some 75 years later.

“You need to find a story that tells a bigger story. I discovered the story of the murder of Pamela Werner while reading an academic biography of the famous American journalist Edgar Snow who became well known in China in the 1930s. A small footnote stated that his neighbour had been Pamela Werner, a young English woman murdered in 1937 and whose killing was never solved. The footnote mentioned that Pamela’s father was a suspect, along with a notorious ‘sex cult’ run by a rather ragtag group of dubious foreigners in Peking. That grabbed my attention!” says French, who took part in the recent Singapore Writers Festival.

Pamela, the adopted child of ETC Werner, a former British consul to China, was the victim of a grisly killing on a frozen night in the dying days of colonial Peking. Her body was found in the morning near the Fox Tower, badly mutilated, her heart ripped out through her rib cage.

The murder occurred at a highly critical juncture in China’s history. Japanese troops were surrounding Peking preparing to seize China’s richest city after Shanghai and Tientsin. In those days, the capital was Nanking.

“The foreigners in the legation quarter were beginning to ask if the legation was the safest place in Peking. A gruesome murder like this was the worst them that could have happened.

“There was already a sense of fear among the foreign residents, as they knew the invading Japanese troops were approaching Peking. But they had no idea how bad things were going to get in the days to come,” French says.

The legation was Europe in miniature, with European road names and electric streetlights. An American or a European could still live like a king in this city, with servants, golf, races and champagne fuelled weekend retreats in the Western Hills just outside Peking.

“My great grandfather used to visit the legation in the 1920s as a naval officer of the British navy, which was then based in Shanghai. You could have mistaken it for London or New York.”

Though young Pamela grew up outside the legation quarter, she enjoyed the quarter’s skating rinks,hotel tea dances, Hollywood movies and big-band music. A fluent Mandarin speaker, she also regularly visited the teeming food market of Soochow Huthong and ate at the cheap Chinese restaurants patronised by Chinese University students.

“She was a white girl who enjoyed both the European lifestyle of the quarter and the life of Chinese Peking,” writes French, who thinks ofher as an independent, self-contained character.

Among the foreigners living in Peking in the 1930s were scholars, diplomats, journalists and businessmen. There were also criminals inhabiting the city’s underbelly known as the Badlands, an area ruled by foreign criminals made up of mostly White Russians (as opposed to Red Russians) who had fled the Russian Civil War. The Badlands were home to pimps, prostitutes and drug dealers.

Solving the case meant months of painstaking research at the National Archives in London. French came across useful files that explained the proceedings of the investigation of the case. The files were full of revelations.

“Many in the Foreign Legation Quarter in Peking assumed the killer must have been Chinese. A murder of a white person by another white person was rare in Peking at the time,” he says.

Through his research, French managed to identify a gang of White Russians involved in the killing of Pamela, which took place in a White Russian brothel in the Badlands. They dumped the young girl’s body on the freezing ground at the Fox Tower, a place known for bad spirits and sorcery.

Seven months after the murder, the Japanese troops invaded Peking and took control of the city. The investigation into the murder case ground to a halt.

“The moment the invasion took place, it was impossible to go back. It was full-out war, the start of the Second World War. That left the British colonies of Singapore, Hong Kong and Burma vulnerable to Japanese invasion,” says French, adding: “Fortunately, all the notes on the investigation went back to London.”

To reconstruct the event, French needed to track down surviving residents from in and around the legation who knew about the murder case. As teenagers then, they would now be in their 80s and 90s. He found seven – Russian, Briton and Chinese nationals – living in Singapore.

“They all say they were scared at the news of Pamela’s murder. The killing drove up the level of panic and fear in the legation. But they all had theories that I found useful. “One woman I spoke to – she died just recently – told me her mother worked in the Badlands. After the murder, whenever her mother saw those men, she would tell her, ‘don’t talk to them’.”

The case was never solved.

With the Japanese invasion and later the civil war, the police didn’t pursue the case and it was later forgotten, especially after the foreigners left Peking in 1941.

“The British kept quiet about the case because it would have been an embarrassment had the killers been identified as foreigners. They actually wanted the killers to be Chinese, so that they could say such an act was committed by some barbaric Chinese.”

But Pamela’s case has left a sort of a legacy, French believes. There were echoes of that same reticence in British government circles over the recent high-profile murder of British national Neil Heywood by Gu Kailai.

“Again the British government didn’t have much to say about the case, mainly because they didn’t want to strain trade relations with China given the faltering British economy. And we actually don’t know what happened; if Heywood was killed, or why he was killed and how. We never saw the body as it was cremated within hours after his murder. And we don’t know if Heywood was trying to threaten the family for money. A crime happened. Wrapped around that crime is politics. This time we see it played out in real time,” he says.

The reporter attended the Singapore Writers Festival courtesy of the city-state’s National Arts Council.